Dr. Anthony Todd Carlisle on Family Legacy

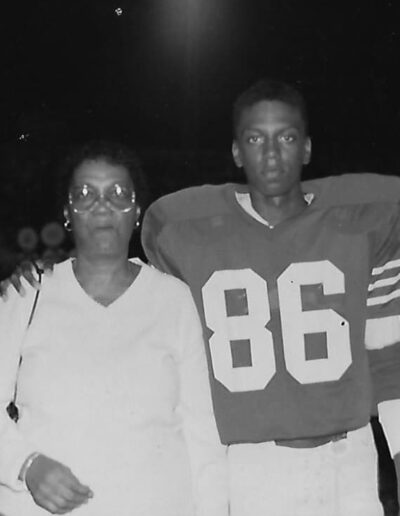

Family

When I think of family, I think of fragmentation.

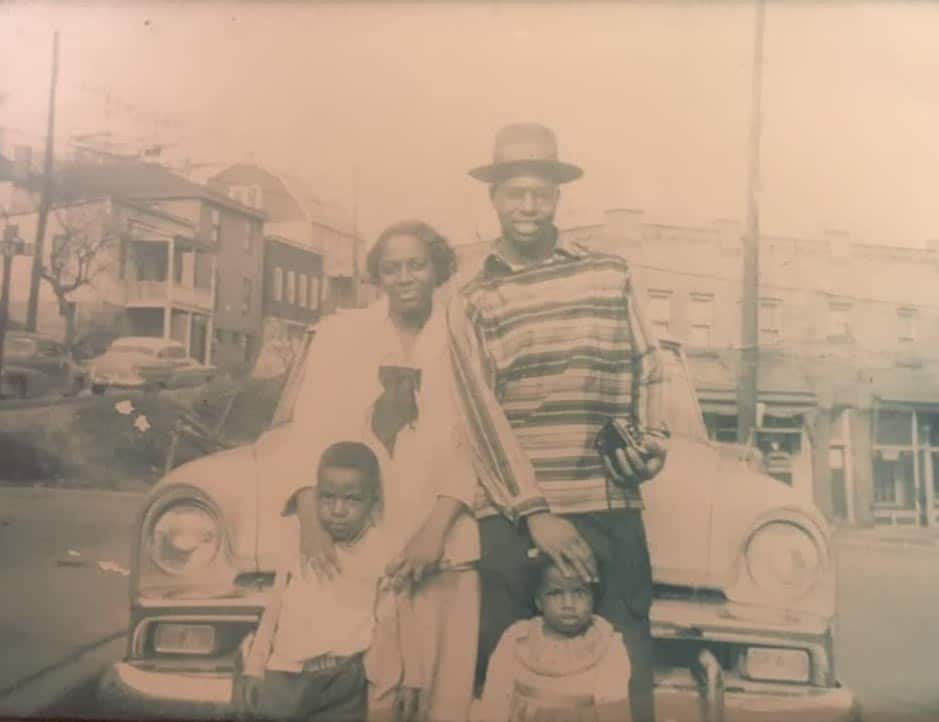

I was nurtured in the Pennsylvania mill town of Ambridge, raised by my maternal grandparents, Perry and Ellen Carlisle. My mother, Janice, moved down the road to Pittsburgh and my father, Butch, lived in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

It was a strange relational setup. I viewed my grandparents as parents, my aunts and uncles as big sisters and brothers. I did view Janice as my mother, but the word “mom” always became lodged in my throat. That title was reserved for my grandmother. As a child, I called my biological mother Jan Jan, eventually Janice, but often I would not use any signifier to specifically address her. Janice wanted me to call her “mom’ . . . but it was just too awkward. When I saw my father, I addressed him as Butch, and there was no expectation of anything else.

I grew up pretending to be a son to Perry and Ellen Carlisle—it was cleaner and easier to explain to people. Of course, Perry and Ellen viewed me as one of their grandchildren, just the one they had to take care of because my parents could not or would not.

My mother had me ten days after her eighteenth birthday. My father was six years older. When my grandparents found out my mother was pregnant, a meeting was held that included both families. The only question my grandparents had for Butch was if he planned to marry their daughter. Butch was not. And with that answer, he was no longer welcome by my grandparents.

Butch eventually left Ambridge and created a life with the woman he did marry, and fathered two additional children—my brother Sean and sister Shenita. He already had another child—our oldest brother, Damont.

As far back as I can remember, I was told that my grandparents raised me because Janice was not equipped for childcare. There were whispers of drug abuse. Years later, when my grandmother was in a nursing home and Janice was dead, I asked how I came to be with them. My grandmother said the plan was that Janice—who moved to Pittsburgh to attend nursing school—would come back and get me. That never happened. What did happen was that my mother became more and more dependent on drugs (crack cocaine) and alcohol. She died at 53 in 2004.

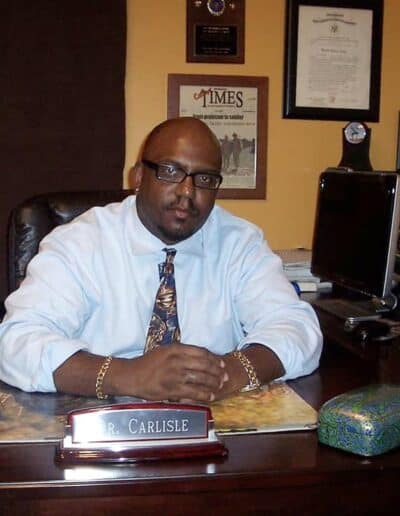

Legacy

I remember how my grandfather, Perry, often lamented that his good name had been run into the ground by his three oldest children, which included my mother. As I sat and listened to his repeated railings, I told myself that I would never bring shame to the family name. The irony is that Carlisle wasn’t my grandfather’s real last name. His absentee biological father’s birthname was Blackmon. Perry would take the name of his stepfather, and he wore that name with pride.

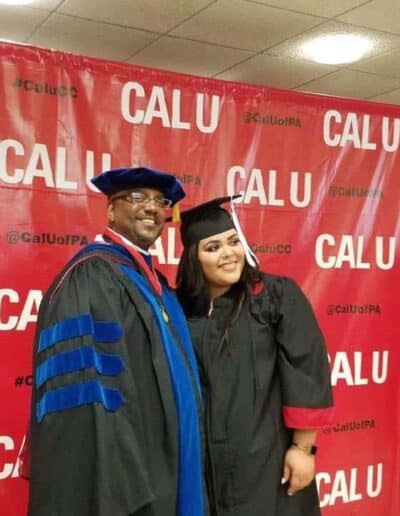

When I became a father, I thought about legacy in a different way—not so much about my last name but my actions. My wife, Amy, and I wanted our children, Arielle and Amya, to always be proud of their parents. We set to create a legacy at home and in our work that would honor our daughters, paving a way for them into adulthood. Throughout their lives, we thought it important to remind our now grown children that they stand on the shoulders of people who survived and carved out lives in some of the worst conditions. They understand that their immediate ancestors were not far removed from this nation’s injustices. My mother drank from segregated water fountains. My grandparents grew up amid twentieth-century Jim Crow. Their parents and grandparents survived the immediate backlash of Reconstruction. My children are products of survivors. Arielle and Amya have that same strength within them to survive any obstacle and thrive in any situation. I am certain they will carry on that strength and our good name.

Experiences

I can always remember the pull and tug of what it meant to be Black in America. In 1977, when I was nine years old, my grandparents allowed me to stay up late for five straight nights to watch Roots. I got a lesson of what it meant to be Black in America, and how we were viewed. I was drawn into that miniseries unlike anything I had experienced in my life. I remember watching Kunta Kinte being stripped of his name, eventually capitulating and becoming Toby. I remember watching with horror as Kizzy was ripped from her parents even when her name meant “stay put” . . . the anguish it caused her mother.

I remember discussing race issues with my best friend, Shawn, a white kid across the street. We had a spirited debate about slavery. In his twelve-year-old view, Shawn argued slavery was a good thing for Blacks because “we” were better off in America than if we had stayed in Africa (he’s evolved, of course). I debated the opposite, although I don’t recall my exact points or how the discussion ended, but it didn’t matter. The debate started on false premises—the inferiority of Africa, African descendants, and superiority of Western culture.

I remember being called a nigger during baseball practice by some white kid just riding by on his bike. As a teenager walking through my town by myself, a group of grown men, for no reason at all, started to taunt me with nigger. And I remember sitting in a ninth-grade English class and my teacher making a point to highlight me as something different than the other students by saying, “You’re a minority. What do you think on this topic?” I thought little of the topic. I thought I wanted to disappear. She made me an “other.” Knowing that you are seen differently, often in an inferior light, is a message most Black people begin experiencing early in their lives. Images everywhere promoting whiteness and trashing darkness. Encounters with white people, in formal and informal settings, often tend to remind us of “our place.” Black folks spend a lifetime trying to unlearn these lessons of inferiority. Class is always in session.

-Todd Carlisle, author of The Souls of Clayhatchee

Recent Posts

Summer Reading List 2024

Summer Reading List–

12 books that I am adding to my TBR list this summer and 12 Hidden Shelf titles that you should add to yours!

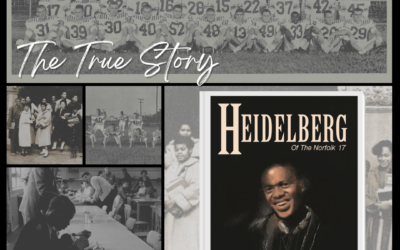

Black History– On This Day in 1959

Black History – On This Day in 1959

The Norfolk 17–February 2, 1959

Sixty-five years ago today, seventeen cautiously brave Black teenagers rocked the foundation of the racist South, accomplishing what many at the time had thought impossible … ending segregation at six public schools in Norfolk, Virginia. If getting there had been a war, being there was horrendous.

2023 Holiday Gift Guide

Unique and creative gifts ideas for the 2023 holiday season!