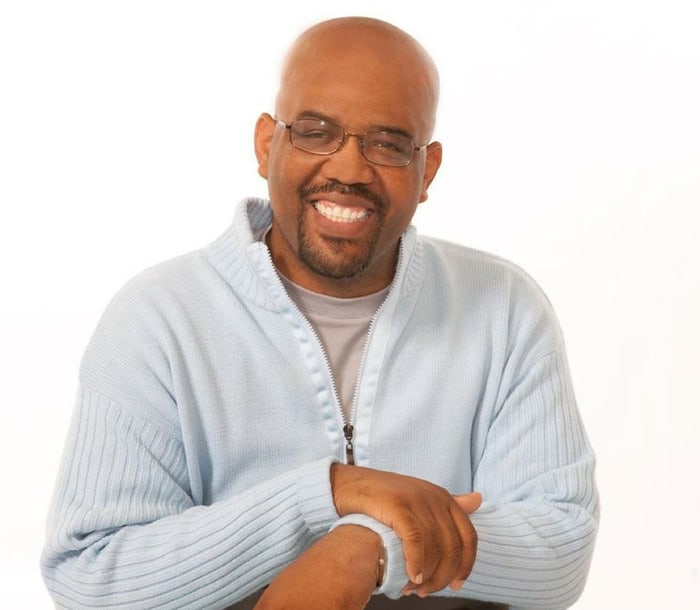

Brian C. Johnson Interview

Author and advocate, Brian C. Johnson, has committed himself personally and professionally to the advancement of multicultural and inclusive education. His newest work of historical fiction, Send Judah First, is based on the life of of Belle Grove Plantation’s head cook from 1817 to 1836. In Send Judah First, Johnson beautifully expounds upon the two historical documents that mention Judah and illuminates the life of this otherwise erased soul.

Purchase your pre-sale copy on Amazon today.

How does Send Judah First differ from other books you have written?

I had never imagined writing historical fiction. Most of my writing and research, though, has centered around mitigating/overcoming the “tensions” of difference.

What was it about the historical figure, Judah, that captivated you?

In the opening pages of the story, you’ll read how I became acquainted with Judah. I live my life for significance. I want to be remembered—my life to matter to someone (other than my wife and children). I want to make an impact. It pains me to think there are so many millions of people who will go unnamed, unremembered, glossed over simply because someone decided to slap the label SLAVE on them.

What picture do you paint of Belle Grove Plantation in the early 1800s?

Simply put, Belle Grove was a farm. The Hites were “fortunate” enough (by 1800s standards) to own workers for that farm. The sad part of this history is that we don’t know much of how things operated daily at Belle Grove. I tried to create a storyline that imagined what could have been—a married couple raising children and creating a family. Similarly, I wanted people to see that same humanity in Judah, Anthony, and their children.

What challenges did you face it writing Send Judah First?

The first things were internal struggles. As an avid reader of narratives of the enslaved, I was intimidated by Alex Haley’s Roots. That book turned TV miniseries stands at the pinnacle of slave narrative literature and media. I wrestled with not wanting to compete with Haley. Similarly, Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup has captured contemporary thought about plantation life. Northup and Haley intimidated me so and as a neophyte writing historical fiction, I wondered if I had the mustard to be able to tell the story.

Externally, there has been a lot of discussion in the modern press and on Twitter about how audiences are tired of seeing “black people in pain” [poverty, slavery, drug addiction and crime]. Thinking of this, then, in telling a slave narrative, what could I offer that’s new? This is why I introduce a love story of sorts. Judah was forced to marry Anthony, perhaps for capitalistic reasons on the part of Master Hite, but, in time, she grows to love him and wanted to create a life with him (despite the circumstances). That is a side we never get to see.

There was yet one more challenge I want to acknowledge—that being Judah herself. This is going to sound weird, but I know writers will get this. In the process of writing this book, I became so close to these characters. I believe Judah spoke to me, willing me to tell her story. There were many nights where I could hear her telling me to get up and write as she downloaded her stories to me. My wife can tell you that there were occasions I awoke to tell Judah to “shut up so I can sleep.” On the days when I took breaks, I felt like I was letting her down.

What do you hope readers take away from Send Judah First?

During my first visit to Belle Grove, I learned that “slave” was not an identity; it was a title. Judah (and countless others) were ENSLAVED—a condition forced upon them. I hope readers can learn to affirm the dignity and humanity of these purchased/kidnapped souls and to welcome them back from obscurity.

How can readers honor the lives of enslaved people who seem to be erased from history?

The enslaved were people too. We live in an era where tracing our genealogy and family ancestry are popular. Genealogy is more than DNA percentages, names and dates. It’s the stories, the medical histories, the traditions that can come alive—these are the things that make us who we are. When I started tracing my family ancestry, my mother told me to “let sleeping dogs lie” as she didn’t necessarily want me to unearth sordid details. I explained, those details are our truth and we should not hide from nor run from the facts. My hope for readers is that this hidden side of American history has fruit for our benefit today.

What is your personal favorite recipe from the back of the book?

I am a BIG fan of the glazed apples. Just earlier this week, I made a similar dish using fresh peaches. My sweet potato pie has earned recognition at our church’s annual pie baking contest, so I’d say that one is a favorite also.

Recent Posts

Black History– On This Day in 1959

Black History – On This Day in 1959

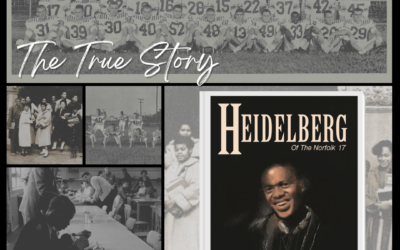

The Norfolk 17–February 2, 1959

Sixty-five years ago today, seventeen cautiously brave Black teenagers rocked the foundation of the racist South, accomplishing what many at the time had thought impossible … ending segregation at six public schools in Norfolk, Virginia. If getting there had been a war, being there was horrendous.

2023 Holiday Gift Guide

Unique and creative gifts ideas for the 2023 holiday season!

2023 Hidden Shelf Holiday Catalogue

2023 Hidden Shelf Holiday Catalogue. Treasured Gifts to Last a Lifetime.